Words that Help Heal Body Shaming and Bullying

Valerie Wansink

[Forthcoming, International Journal of Child Health and Human Development 2023; 16(3), August]

Abstract:

What can a parent or health professional say to a body shamed and bullied child? This research elicited and categorized the words that were reported as being most memorably hurtful and helpful to 341 young people (79.5% female; average age 25.03 years) who had been body shamed. The most memorably hurtful comments generally involved either vivid comparisons or derogatory nicknames. Fortunately, the supportive words of health professionals, peers, and parents can heal. They included 1) reframing comments that redirected attention toward a “silver lining” of an attacked feature (such as being “feminine” or “healthy” instead of “fat”), 2) impact-related comments that emphasize how a physical feature influences or is admired by other people (such as how one’s eyes or smile “light up the room”), and 3) identity-related comments that redefine one’s physical identify or self-concept (such as “striking” or “mesmerizing”). Knowing the types of words that were helpful in healing can also be useful to parents and peers as they prepare to comfort a loved one.

Keywords: Bullying, Body shaming, recovery, resilience, parents, obesity, adolescents, cyberbullying, school bullies

Acknowledgements: This project was self-funded. Thank you to the Girl Scouts of America (NYPennPathways), the students and faculty at Lansing (NY) Central School Districts, and the Cornell University Borloug Scholars Program for helpful feedback on this project.

Correspondence: Valerie Wansink, Lansing Central School District, 159 Reach Run, Ithaca, NY 14850, [email protected]; [email protected]

"What Can I Say to Help?"

| |||||||

Introduction

Body shaming, fat shaming, and weight bullying can have a dramatic impact on a person’s self-esteem (1,2). A key question in this exploratory research is what are types of name calling or verbal bullying have a long-lasting negative impact on a young person (3) and what types of comments can be made by a supporter – a professional, parent, or peer – to help counterbalance or temper this impact? In short, what words hurt and what words heal.

Body shaming can cause lasting psychological damage (4). Although this can happen at all ages (5), it seems most pronounced and harmful when a person is young (6,7). Body shaming and bullying is correlated with low self-esteem, poor school performance, absenteeism, self-handicapping, and even suicide (4,8), and being bullied as a child is a powerful predictor of exaggerated weight gain in some people (9). Shaming and bullying is no longer just a problem in middle and high school (10). It has expanded to the internet and to social networking sites (11). It has a 24/7 impact.

Words hurt, but it is not clear what words hurt the most and which one will have the deepest and most lasting scar (15). Whereas experimental research shows that even short-term teasing can negatively alter one’s mood (16), more intense and malicious verbal bullying could last for many years (17). It can lead to shame (18), stress (19), eating disorders (20), obesity (9), binge eating (21) and depression (22). This can affect all genders and is believed to be both more prevalent and more serious than in the past (1) due to the large prevalence of 24/7 social media (23).

Research has not yet codified the actual types of words that are most memorably painful to a person (12), or what is most memorably helpful to their recovery. Knowing this could aid potential supporters – peers, parents, or professionals – in helping a bullied person better counter (13) and cope (14) with body shaming. Moreover, these findings can be useful to the friend or family member who is asking themselves “How do I help?” or “What can I say?”

To determine how body shaming and fat bullying might influence a person long after it happens, a survey targeted at body shamed individuals asked them to explain what was said to them that was most hurtful and what did supporters say to them that was most helpful in the healing process. After analyzing these open-ended answers, this exploratory research first examines “What types of words hurt the most?” Next, in looking toward gender-inclusive solutions, we also determine what types of words are most helpful to someone who is suffering from having been shamed. That is, what types of words help the most?

Methods

An online omnibus survey was targeted at recent high school graduates (18 years and older). They were recruited through a news release that described the purpose of the study and which was sent to youth health and lifestyle bloggers. A survey link was provided to bloggers and others who circulated this link through social media and through personal listservs. These bloggers and listserv managers then promoted the topic and the link in ways that were intended to attract people who were familiar with body shaming.

Upon arriving to the survey’s website, visitors were told “You are invited to participate in a research study that seeks to understand the issue of body shaming (the action or practice of humiliating someone by mocking or making critical comments about their physical appearance) among young adults and how to preempt, cope, and stop it.” Those who indicated they were 18 years or older and who signed their consent were then allowed to begin the survey. The survey and study had Institutional Review Board approval from Cornell University.

The questions were generally intended to refer to body shaming that occurred in adolescence (middle school or high school). Of those people who completed most or all of the survey, 61.4% were between 18-22 years of age. This was the targeted age range because it gave some temporal distance from the event, and it has been the general age-range in cyber bullying and teasing research (30). It was believed that their initial experiences with body shaming would be recent enough to be remembered, but distant enough to allow for reflection (31).

They were asked open-ended questions about their specific experiences with body shaming, including the hurtful comments that were made as well as the helpful comments given by supporters. They were also asked exploratory close-ended questions, and they were asked to indicate what level of body shaming they had experienced.

Of the 341 people who started the survey, 166 (48.7%) completed all or most of the survey. The median time spent on the survey was around 10 minutes, and those who provided the most in-depth open-ended responses took the most time with the survey. Of those completing the survey, 79.5% identified as females, one as transgender, and the rest as males. The average age of those completing the survey was 25.03 years (range from 18-62 years). Based on the responses of all genders and ages, we developed an inclusive coding system so the comments of the respondents could be content analyzed and then categorized into discrete categories. A Q-sort procedure was used to determine the coding categories for each open-ended question. After determining the coding categories, two coders in the age range of interest (one was the author) coded the open-ended responses. This was repeated on two separate occasions to increase intra-coder reliability. Any resulting disagreement between the two coders final responses was then discussed and resolved.

Results

Inclusive coding categories were developed for both hurtful and helpful comments. Categories of hurtful comments included vivid comparisons and derogatory nicknames. In contrast, categories of helpful comments included reframing comments, impact-related comments, and identity-related comments. After first examining the physical features that were targeted by attackers and the features that were complemented by supporters, we will then focus on the types of comments that were most memorably hurtful and helpful.

Table 1:

The Physical Features Most Mentioned by Attackers and by Supporters

Body Shamed Features Most Targeted by Attackers

• Overweight – 25.2%

• Height – 8.5%

• Legs -- 7.8%

• Underweight – 7.1%

• Stomach – 3.9%

• Skin – 2.6%

• Hair, Breasts, Buttocks, or Hair – each 1.9%

• Hips or Body Hair – each 1.3%

Positive Features Most Frequently Mentioned by Supporters

• Eyes – 18.1%

• Smile – 11.4%

• Legs – 8.4%

• Body – 7.2%

• Hair – 6.0%

• Toned/Muscles – 4.8%

• Skin – 3.6%

• Healthy – 3.0%

• Handsome – 2.4%

• Athletic – 1.8%

• Teeth and Lips – each 1.2%

The physical features most mentioned by attackers and by supporters

Of initial interest are the specific physical features mentioned by attackers and those mentioned by supporters. As Table 1 indicates, most of hurtful body shaming comments were targeted at specific physical features, such as being fat (25.2%), short (8.5%), or skinny (7.1%). Legs were also a frequently ridiculed (7.8%), either legs, including thighs, calves, or ankles (7.5%). In total, nearly a third (32.3%) of the most hurtful comments specifically focused on a person’s weight, with 78% focused on being overweight.

Interestingly, people who had been body shamed also vividly remembered the positive physical features they have which supporters had complimented – in some cases nearly 50 years earlier. These generally focused physical features unrelated to those that were bullied – such as eyes (18.1%) or smile (11.4%), which (along with teeth and lips) comprised nearly a third (31.9%) of these features.

Table 2:

Categories and Illustrations of Memorable Negative Comments

1) Exaggerated Comparisons

• That I am even bigger than a man

• “You have bigger thighs than me” (it was a guy)

• “You look like a fullback”

• That I look like a skeleton

• “You look like you're pregnant”

• Chicken skinny

2) Derogatory Nicknames

• Tubby-tubby two by four

• Bubble Butt

• I was called ‘Chihuahua’ because I'm short and Mexican American

• Hairy monkey

• Buddha Belly

3) Other Examples of Hurtful Comments

• I'm too fat for any guy to be attracted to me

• "We met our fat chick quota already"

• That you can’t tell the difference between my front and back because I am quite skinny and have few curves.

• When the boys in 7th grade called me “whale” relentlessly. These were boys I had crushes on.

Hurtful negative comments include exaggerated comparisons

Knowing the physical features that were the target of the attack made on a person is useful, but it was often how the attack was made that was so hurtful. That is, a person may very well be aware that they are relatively heavy or short, but it is the vividness of the attack that can leave a lasting scar.

One category of hurtful comments that stood out were those that made an exaggerated comparison or analogy. These included comparing a person’s size to that of a whale, comparing one’s thighs to trees, or one’s stomach to that of a pregnant woman. Although being comments about being overweight comprised 25.2% of all comments, 7.1% were shamed or bullied for being underweight, such as being compared to a skeleton or as having “chicken skinny” legs (see tables 1 and 2). For instance, one girl remembered people describing her like a board, saying “They said they can’t tell the difference between my front and back because I am quite skinny and have few curves.”

A second common category of body shaming that was commonly mentioned included derogatory nicknames (see table 2). This category frequently included alliterative names like Buddha belly or references to popular culture (HairyPotter). One person recalled being called "Chihuahua" because they were short and Mexican American.

Hurtful comments were sometimes specified as coming from a relative or from an admired person. For example, these could include a father joking about a girl’s hair, a mother commenting on breasts, or a brother making animal sounds like “oink” or “moo”) One girl hurtfully recalled a time “When the boys in 7th grade called me "whale" relentlessly. These were boys I had crushes on.”

Helpful positive comments include reframing and redirecting

One category of helpful comments were reframing comments, which reframed the physical feature that had been attacked. It did not deny what was said but instead reframed it by focusing on one’s “hourglass” figure, one’s muscle tone, or as one being “healthy.” In addition to reframing, other memorable comments specifically redirected one’s focus onto physical features that were unrelated to the features that was shamed. As Table 1 indicated, the most frequently mentioned examples of this were a person’s eyes and smile.

A second category of helpful comments were impact-related comments that emphasized how a person’s features impact other people in a positive way. These included comments such as how a person’s smile, eyes, or laugh was “contagious,” “infectious,” “lit up a room,” or “radiated joy.” It also included comments that showed that they had traits that other people envied or wished they had (such as “I wish I had your eyes”). For example, being told you have a wonderful smile might be memorable partly because of who said it. One person said, “My husband always describes me to others as the pretty girl with the big smile.” Another person simply said, “My father complimented my smile.” These were very simple but helpful comments coming from an important person.

A third category of memorable comment were identity-related comments that generally centered on a single, evocative word that reinforced an overlooked part of their identity more than any one physical feature. That is, they were “mesmerizing,” “striking,” “exotic,” or “feminine.” Even though these were sometime stated in conjunction with other words (“mesmerizing beauty”), they were seen by a person as a more general part of a positive identity. Whereas the adjectives in the negative body shaming comments were general and not creative (such as “really fat” or “very short”), the positively remembered comments were more vivid, creative, or artfully used. Some became a tent pole that reinforced a new, positive identity.

Discussion

As an exploratory study, this usefully specifies and classifies the types of hurtful phrases used in body shaming and bullying, but it also uniquely classifies and provides examples of helpful types of healing phrases. By doing so, it provides a foundation to motivate new research in these areas of memorably hurtful comments and helpful comments.

Words hurt, but these preliminary findings show that some types of words leave a more salient and lasting pain than others. Follow-up discussions indicated it was not only a general label that hurt (fat, short, skinny, and so on) but – more specifically – it was derogatory nicknames (thunder thighs and Zit Thomas) and vivid comparisons (whale and Buddha belly) that were especially painful. This might be because both hurtful categories are very personal, very specific, and they can be easily triggered. That is, the mention of a Harry Potter movie can trigger “Hairy Potter” to mind, or the mention of “whale watching” can trigger a memory of being called a whale and hearing someone make whale imitations during school lunch.

Table 3.

Categories and Illustrations of Memorable Positive Comments

1) Reframing Comments

• Curvy/Hourglass/Voluptuous

• Toned/Muscular

• Healthy

• Athletic

2) Impact-related Comments

• “Your smile is contagious. Your smile just radiates joy”

• “Your eyes are captivating and infectious”

• “I wish I had your body/eyes/smile”

3) Identity-related Comments

• I have an exotic appearance

• That my beauty was mesmerizing

• I am striking looking.

• “You have a really bright smile or feminine hands”

4) Other Examples of Helpful Positive Comments

• I still have that unique beauty from childhood

• That I'm not too fat, and I'm not too skinny. I'm just right

• My chest was very powerful and very sexy

• “Wow your abs look good, I can tell you really work for them."

• Someone said I reminded them of a very pretty celebrity.

An encouraging insight from these findings is they also suggest what a health professional, parent, or peer might say to help counter the body shaming messages. Table 3 usefully presents the types of positive phrases that have tended to stick with people over the years. One strategy can be to reframe negative words to focus on either a silver lining or on unrelated physical features (see Appendix for a worksheet on how to do so). A second strategy can be to make impact-related comments that emphasize how a physical feature influences others (such as how one’s eyes or smile that “lights up the room”). A third strategy can be to use identity-related comments that can positively redefine one’s physical identify or self-concept (such as being striking or mesmerizing). Not all three strategies will be appropriate for any one person, but one may be more appropriate than the other two.

Implications

Body shaming can be fought on three fronts: 1) By the individual being attacked, 2) by supporters (professionals, parents, and peers), and 3) by the institution in which the shaming occurs. First, for an individual who may be vulnerable to body shaming, knowing that there are some basic categories of comments that are universally hurtful can be useful to know. It shows them they are not alone. It shows that the person is not isolated in the way they are attacked and in how they are attacked. Knowing that there are many people who have recovered from being called the same types of shaming and bullying could make a person feel less alone and more hopeful.

Second, for supporters – professionals, parents, and peers – it should be helpful to know what types of helpful words and what categories of comments might be most memorable and useful to the recovery of their loved one. This is important for anyone who has ever thought “What do I say?” Knowing these categories of helpful words, can give them confidence to play or to rehearse what to say that would be most helpful to the specific case of their loved one. It is important to realize that they are not helpless and what they say can have a lasting impression (32). The Appendix is a worksheet titled “What Healing Words Can I Say?” Supporters can use it to think more carefully about which of the three approaches and which particular words could be useful when preparing for a conversation with a patient or a loved one.

Third, because schools are one common area where in-person body shaming can occur, they can also be a context where it might be effectively addressed. Counselors, nurses, teachers, and lunch staff, could be given easy-to-remember guidance on the types of words (comparisons and derogatory names) that are hurtful and the types of words (and strategies) that can be helpful in recovery (see Appendix). Most easily, giving these front-line workers a basic framework – such as “recognize and reframe” – could be useful in reducing body shaming and in helping comfort those who are hurt. In a bigger way, lunchrooms themselves can be altered in ways that help students eat healthier and begin addressing problems with – which was about one-third of the comments mentioned here (33–36).

Limitations and future research

This exploratory study usefully highlights several topics that have been missing from earlier literature. Most of those who took this survey were college-aged people who were body shamed during adolescence. Given their closeness to this emotional issue, they could have had the tendency to either exaggerate or underplay (repress) what really happened.

One attempt to minimize the limitations of retrospective studies was to survey people who were close in age to the situation. Many of the people who responded to this survey were college students. This too, however, comes with its own limitations. Such a population represents a well-educated group sample compared to the larger pool of those who were body shamed. Being well-educated might moderate some of the identity problems associated with being body shaming if it enables a person to build upon a professional identity or on other opportunities. That is, success in one area could help ameliorate one’s feelings of shortcoming because they were body shamed.

This raises the importance of capturing the richness of the experiences of body shamed people to better understand the individual ways they dealt with the experience: how they dealt with the shamers, what self-talk worked best for them, and how they were able to heal and move on. There is a great deal of power in analyzing qualitative responses with an eye toward providing specific roadmaps and tools to help others move forward.

Conclusions

Body shaming, weight shaming and bullying can scar a person for life (37). These preliminary findings in this study give insights for immediate action. They show supporters – mental health professionals, parents, and peers – the ways they can reframe negative words toward silver linings. They show them how to make impact-related comments that emphasize how a physical feature influences others (such one’s eyes or smile that “lights up the room”). They also show how identity-related comments can be used to positively redefine one’s physical identify or self-concept (such as “striking” or “mesmerizing”). As childhood obesity increases, body shaming may become even more severe. Hopefully the insights from this research and the words that you generate from the worksheet in the Appendix can help.

Acknowledgements

This project was self-funded. The authors would like to thank the Girl Scouts of America (NYPennPathways), the students and faculty at Lansing (NY) Central School Districts, and the Cornell University Borloug Scholars Program for helpful feedback on this project. The authors declare that no funds, grants, or other support were received during the preparation of this manuscript. The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose, nor any conflicts of interest. The Office of Research Integrity and Assurance (ORIA) at Cornell University declared this study exempt from full Institutional Review Board review #06-1102000312. The study conceptualization and data collection were conducted by Valerie Wansink and Brian Wansink, and Valerie led the data entry and coding. Both authors prepared the first draft of the manuscript, and both authors read and approved the final manuscript.

References

1. Gam RT, Singh SK, Manar M, Kar SK, Gupta A. Body shaming among school-going adolescents: prevalence and predictors. Int J Commun Med Public Health 2020;7(4):1324.

2. Schlüter C, Kraag G, Schmidt J. Body shaming: An exploratory study on its definition and classification. Int J Bullying Prev 2021 Nov 9. URL: https://link.springer.com/10.1007/s42380-021-00109-3.

3. Ali MM, Fang H, Rizzo JA. Body weight, self-perception and mental health outcomes among adolescents. J Ment Health Policy Econ 2010;13(2):53–63.

4. Green M, Lankford RD. Body image and body shaming. New York: Greenhaven Publishing, 2016.

5. Maiano C, Ninot G, Bilard J. Age and gender effects on global self-esteem and physical self-perception in adolescents. Eur Phys Educ Rev 2004;10(1):53–69.

6. Bryson SL, Brady CM, Childs KK, Gryglewicz K. A longitudinal assessment of the relationship between bullying victimization, symptoms of depression, emotional problems, and thoughts of self-harm among middle and high school students. Int J Bullying Prev 2021;3(3):182–95.

7. Lunde C, Frisen A. On being victimized by peers in the advent of adolescence: Prospective relationships to objectified body consciousness. Body Image 2011;8(4):309–14.

8. Romano I, Butler A, Patte KA, Ferro MA, Leatherdale ST. High school bullying and mental disorder: An examination of the association with flourishing and emotional regulation. Int J Bullying Prev 2020;2(4):241–52.

9. Bevelander KE, Kaipainen K, Swain R, Dohle S, Bongard JC, Hines PDH, et al. Crowdsourcing novel childhood predictors of adult obesity. PLoS One 2014;9(2):e87756.

10. Clare MM, Ardron-Hudson EA, Grindell J. Fat in school: Applied interdisciplinarity as a basis for consultation in oppressive social context. J Educ Psychol Consult 2015;25(1):45–65.

11. Wang Y, Wang X, Yang J, Zeng P, Lei L. Body talk on social networking sites, body surveillance, and body shame among young adults: The roles of self-compassion and gender. Sex Roles 2020;82(11–12):731–42.

12. Conoley JC. Sticks and stones can break my bones and words can really hurt me. Sch Psychol Rev 2008;37(2):217–20.

13. Orr T. Combatting body shaming. New York: Rosen Publishing, 2017.

14. Chomet N. Coping with body shaming. New York: Rosen Publishing, 2017.

15. deLara EW. Consequences of childhood bullying on mental health and relationships for young adults. J Child Fam Stud 2019;28(9):2379–89.

16. Furman K, Thompson JK. Body image, teasing, and mood alterations: An experimental study of exposure to negative verbal commentary. Int J Eat Disord 2002;32(4):449–57.

17. Menzel JE, Schaefer LM, Burke NL, Mayhew LL, Brannick MT, Thompson JK. Appearance-related teasing, body dissatisfaction, and disordered eating: A meta-analysis. Body Image 2010;7(4):261–70.

18. Novitasari E, Hamid AYS. The relationships between body image, self-efficacy, and coping strategy among Indonesian adolescents who experienced body shaming. Enferm Clínica 2021;31:S185–9.

19. Howard MS, Medway FJ. Adolescents’ attachment and coping with stress. Psychol Sch 2004;41(3):391–402.

20. Iannaccone M, D’Olimpio F, Cella S, Cotrufo P. Self-esteem, body shame and eating disorder risk in obese and normal weight adolescents: A mediation model. Eat Behav 2016;21:80–3.

21. Duarte C, Pinto-Gouveia J. The impact of early shame memories in binge eating disorder: The mediator effect of current body image shame and cognitive fusion. Psychiatry Res 2017;258:511–7.

22. Brewis A, Bruening M. Weight shame, social connection, and depressive symptoms in late adolescence. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2018;15(5):891.

23. Buckels EE, Trapnell PD, Paulhus DL. Trolls just want to have fun. Personal Individ Diff 2014;67:97–102.

24. Edwards NM, Pettingell S, Borowsky IW. Where perception meets reality: Self-perception of weight in overweight adolescents. Pediatrics 2010;125(3):e452–8.

25. Bharathi TA, Sreedevi P. A study on the self-concept of adolescents. Int J Sci Res 2016;5(10):512–6.

26. Preckel F, Niepel C, Schneider M, Brunner M. Self-concept in adolescence: A longitudinal study on reciprocal effects of self-perceptions in academic and social domains. J Adolesc 2013;36(6):1165–75.

27. Salmivalli C. Intelligent, attractive, well-behaving, unhappy: The structure of adolescents’ self-concept and its relations to their social behavior. J Res Adolesc 1998;8(3):333–54.

28. Stodden DF, Goodway JD, Langendorfer SJ, Roberton MA, Rudisill ME, Garcia C, et al. A developmental perspective on the role of motor skill competence in physical activity: An emergent relationship. Quest 2008;60(2):290–306.

29. Wansink B, Wansink V. Body shaming, fat bullying, and their long-term consequences. Ithaca, NY: Working Paper, under review, 2022.

30. Cassidy W, Jackson M, Brown KN. Sticks and stones can break my bones, but how can pixels hurt me? Students’ experiences with c yber-bullying. Sch Psychol Int 2009;30(4):383–402.

31. Cash TF. Developmental teasing about physical appearance: Retrospective descriptions and relationships with body image. Soc Behav Pers Int J 1995;23(2):123–30.

32. Wansink B, Latimer LA, Pope L. “Don’t eat so much:” how parent comments relate to female weight satisfaction. Eat Weight Disord 2017;22(3):475–81.

33. Greene KN, Gabrielyan G, Just DR, Wansink B. Fruit-promoting smarter lunchrooms interventions: Results from a cluster RCT. Am J Prev Med 2017;52(4):451–8.

34. Hanks AS, Just DR, Wansink B. Smarter lunchrooms can address new school lunchroom guidelines and childhood obesity. J Pediatr 2013;162(4):867–9.

35. Hubbard KL, Bandini LG, Folta SC, Wansink B, Eliasziw M, Must A. Impact of a smarter lunchroom intervention on food selection and consumption among adolescents and young adults with intellectual and developmental disabilities in a residential school setting. Public Health Nutr 2015;18(2):361–71.

36. Wansink B. Slim by design: mindless eating solutions to everyday problems. New York: Wm. Morrow, 2014.

37. Eisenberg ME, Neumark-Sztainer D, Story M. Associations of weight-based teasing and emotional well-being among adolescents. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2003;157(8):733.

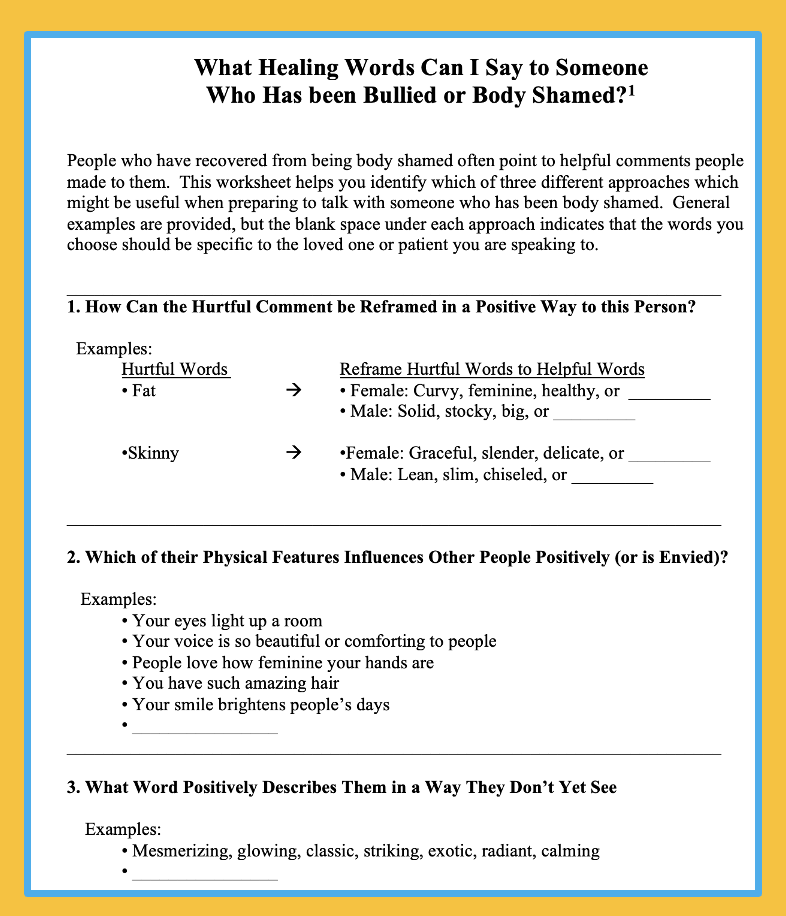

APPENDIX:

What Healing Words Can I Say?

People who have recovered from being body shamed often point to helpful comments people made to them. This worksheet helps you identify which of three different approaches which might be useful when preparing to talk with someone who has been body shamed. General examples are provided, but the blank space under each approach indicates that the words you choose should be specific to the loved one or patient you are speaking to.

________________________________________________________________________

1. How Can the Hurtful Comment be Reframed in a Positive Way to this Person?

Examples:

Hurtful Words Reframe Hurtful Words to Helpful Words

• Fat • Female: Curvy, feminine, healthy, or _________

• Male: Solid, stocky, big, or _________

•Skinny •Female: Graceful, slender, delicate, or _________

• Male: Lean, slim, chiseled, or _________

___________________________________________________________

2. Which of their Physical Features Influences Other People Positively (or is Envied)?

Examples:

• Your eyes light up a room

• Your voice is so beautiful or comforting to people

• People love how feminine your hands are

• You have such amazing hair

• Your smile brightens people’s days

• ________________

___________________________________________________________

3. What Word Positively Describes Them in a Way They Don’t Yet See

Examples:

• Mesmerizing, glowing, classic, striking, exotic, radiant, calming

• ________________

___________________________________________________________